I listened to a panel of speakers discussing the book, The Future of the Professions, this week

in Oxford. Both authors were present and both had the surname Susskind - at

first I thought that they were brothers though they looked very different. Both

handsome men, one of them reminded me of Frankie Vaughan and the other Freddy

of the Dreamers, in other words very, very different. It was only when the thin,

bearded one called the broad-featured one Dad that I got it.

|

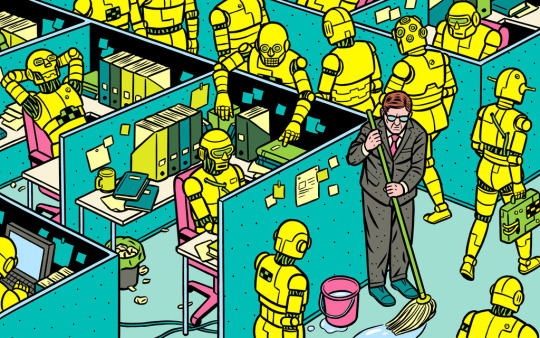

| Illustration by Norwegian cartoonist and illustrator, Kristian Hammerstad, from “Rise of the Robots,” a New York Times Sunday Book Review article, May 11, 2015. |

Their book was praised, criticised and analysed by three

academics: one from the Internet world, another from the religious dimension

and the third a sociologist. The latter was the most critical; she quoted the

use of MOOCs, the free on-line courses where only 5% of those who started

actually completed the courses. The authors’ response was that enrolment for one

of Harvard’s MOOCs attracted more applicants than the total number of students

of Harvard – ever. So 5% completion of a free course was pretty good.

The authors were both cogent and convincing, arguing that it

is wrong to look only at jobs in the professions – the jobs should be broken

down into tasks. They cited the example of the tasks that nurses now do that

doctors previously did. But their main point is that technology is creating

solutions that are superior to those offered by the professions and that this

trend will continue. Expert systems could soon be better at diagnosis than the

GP and could also be programmed to be empathetic. Similarly, lawyers cannot

access and process the vast databases of trials and case law at the speeds and

scope that a clever computer can. They cited a simple and existing example:

millions of disputes about transaction on eBay are now settled via its

resolution system with no lawyers involved.

I think that they are right, particularly where the tasks

are simply knowledge based – as many professional tasks are. Progress in this

direction will be spotty, but could be rapid. The NHS already has an online

symptom checker. I’ve tried it. It is very basic and does not even link to the

patient’s records, but when it does so, and when it incorporates AI and access

to the massive amount of data on treatments, it is likely to exceed the

competence of the average GP with his or her salary of £100,000 per annum.

There are problems of course: ownership of data being one

and culpability in the event of incorrect diagnosis being another. But these

problems exist for the existing doctors too and it is conceivable that future

automated solutions may have greater access to data and hence provide superior diagnoses.

Sometimes a little voice in my head says to me, “haven’t we

heard all this future gazing stuff before? Long before, perhaps in the 1970s,

when the computer was going to take over almost everyone’s jobs and robots the

remainder”. That did not happen, or at least not to the extent that some

soothsayers then claimed. But in the meantime technology has made great

strides: computers are so much more powerful and have the capability to learn;

the Internet and Web provide an undreamed of degree of interconnectivity; and

the means of sharing and intelligently mining vast databases has become

feasible. So maybe we are on the brink of a great change which will

revolutionise the professions.

Interesting isn’t it that this revolution will rock the well paid

professionals, possibly leaving the artisans, creative artists, bricklayers and

so on to carry on as before.

As I finished writing this I had need to approach a

solicitor for advice and was shocked by

their charges – almost £300 per hour! Roll on automation and a more equitable

world.

Actually I would rather flip the question of robots by instead talking about the robotisising of the human. It’s apparent for everyone with a smartphone that it has become a third part of the brain or a portable brain. Very few can today do much without accessing the external brain. We have become dependent on social media in order to be confirmed and “liked”. We are expecting more from machines and less from people. Gradually what partially defines a human being, empathy is grated.

ReplyDeleteFor people entering education today as professionals within healthcare will thus be less empathetic. Hence the argument about empathy will be a non-issue.

It has been possible for the last three years to implement AI diagnostic systems (IBM Watson is standing ready to take over) but of course everyone is defending its profession.

However two rationales are going to force medical persons to give in. The first is the escalating cost at NHS and the other is that diagnosing patients today has become very difficult and complex. There are several reasons for this. They are populations have become highly heterogeneous (migration), new diseases coming from travelling (Ebola,Zika, etc) and international trade and mutations.

Moreover all beds in the hospitals and clothes worn by patients will be embedded with sensors, which communicate with the HOC (hospital operating central) by wireless internet.

For many of as elderly it will be a case of the turn of the screw, but for young people growing up who has been computer lobotomised this what they are expecting.

Good points

ReplyDeleteThe day we don't need lawyers is the day we'll need more judges!

ReplyDeleteSue

That's profound Sue, not sure what it means though.

ReplyDelete